A Kind of Loving (1962) may be British director John Schlesinger‘s best film; I don’t know. Cold Comfort Farm is good too, but Darling, Marathon Man and, probably, Midnight Cowboy (which I’ve resisted watching in full) don’t cut it. Loving, based on a novel, is an exquisitely wrought production in which Alan Bates stars as a working-class man who, because of her pregnancy, marries a girl (June Ritchie) whom he inconsistently cares for. For six months the marriage is miserable, but it’s primarily due to the couple’s having to live with the girl’s unpleasant mother (Thora Hird). The acting is superb. Aspiring thespians should study Bates for his range. Ritchie and Hird make the women flibbertigibbets but not just that. The look of the movie is enticing, with Schlesinger savvy at filming space—not outer space, just space—influenced perhaps by Antonioni.

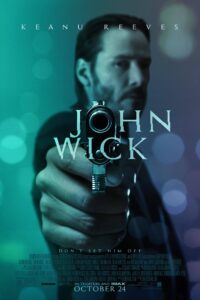

Russian criminals in America beat the excrement out of John Wick, a former hit man, kill his beagle puppy, and steal his car. But Wick is formidable; he arms himself (after all these years) and goes out to settle the score.

Russian criminals in America beat the excrement out of John Wick, a former hit man, kill his beagle puppy, and steal his car. But Wick is formidable; he arms himself (after all these years) and goes out to settle the score.

To me, an action movie nowadays needs to be fluid, non-arty and halfway-sensible or it will be no blasted good—and this is the kind John Wick (2014) is. Tidy, not at all sloppy are the direction of Chad Staheslki and the film editing of Elisabet Ronaldsdottier. . . As John Wick, though, Keanu Reeves moves well but is flat, while surprisingly Ian McShane seems out of kilter. But it matters little since this commercial flick, as John Nolte says on the Big Hollywood site, “knows exactly what it is and what it promises.”

Fiction writer Mark Helprin provides in his short story “The Pacific” the portrait of a woman called Paulette, who is married to a marine lieutenant sailing during wartime (WWII) on the ocean Paulette lives very close to. The Pacific, of course. The woman is a trained welder, spunkily working while her husband is away. Will he return? The ardor of the dutiful in spite of separation, the heavy demands of devotion, war’s threat to marriage—all are themes in this striking piece. And as always, Helprin is fascinated by nature’s display and organizational work and technology.

In “Last Tea with the Armorers,” there is another heroine, Annalise—Jewish and not quite pretty. By 1972 she “had been in the [Israeli] army in one form or another for sixteen years . . .” and has an awful connection with the Holocaust. Unmarried and caring for her father, Annalise does the best she can, with a broken heart. But a possible future marriage is emerging. The dark past gives way to the present, the present to the future. What’s more, belief in God shan’t be rejected. “Armorers” is a unique and lovingly written story.

A Francois Truffaut film, Small Change (1976) is small potatoes.

Full of vignettes, most of them mediocre, about young boys (and one girl), the flick is vapid, intermittently sentimental, even stupid. The old Truffaut charm registers much weaker than it does in The 400 Blows, Jules and Jim, Two English Girls, etc.

(In French with English subtitles)

Related articles

Numerous adults are far from being good role models for young people. A teacher called Jim McAllister—in Tom Perrotta‘s 1998 novel, Election—is one of them. At the high school where he works, McAllister is in charge of the election for student president, a position coveted by the high-achieving, 17-year-old Tracy Flick.

Tracy is nice but has no friends. However, she is much gratified over a sordid affair she is having with McAllister’s fellow teacher, Jack, who is married. McAllister, aware of the affair, dislikes the girl, even though there is not really much to dislike. As it happens, he wrongs Tracy in the election. Shabby behavior here mirrors the kinds of things plaguing adult political elections.

Perrotta’s book is breezy and wise. We never feel superior to the characters, certainly including Tracy, not “just a sweet teenage girl,” McAllister claims. But Tracy, in truth, is a child of divorce, and is let down by the book’s grownups. Election‘s denouement is brilliant in a way that the ending of Alexander Payne’s movie adaptation of the novel is not, for it shows Tracy conciliating with a man, McAllister, who has lost his job and his reputation. She doesn’t need to reject him.