Russian criminals in America beat the excrement out of John Wick, a former hit man, kill his beagle puppy, and steal his car. But Wick is formidable; he arms himself (after all these years) and goes out to settle the score.

Russian criminals in America beat the excrement out of John Wick, a former hit man, kill his beagle puppy, and steal his car. But Wick is formidable; he arms himself (after all these years) and goes out to settle the score.

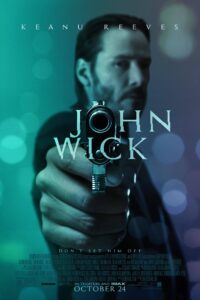

To me, an action movie nowadays needs to be fluid, non-arty and halfway-sensible or it will be no blasted good—and this is the kind John Wick (2014) is. Tidy, not at all sloppy are the direction of Chad Staheslki and the film editing of Elisabet Ronaldsdottier. . . As John Wick, though, Keanu Reeves moves well but is flat, while surprisingly Ian McShane seems out of kilter. But it matters little since this commercial flick, as John Nolte says on the Big Hollywood site, “knows exactly what it is and what it promises.”