In Revanche (2009), from Austria, an ex-con named Alex (Johannes Krisch) works for a scurvy pimp and is secretly in love, and in a sexual relationship, with one of the pimp’s prostitutes, Tamara (Irina Potapenko). Both wish to get away from the pimp and raise enough money to pay the drug-addicted Tamara’s debts, so Alex devises a plan. He’ll rob a bank for some short-term cash, the two will flee Vienna for Ibiza where Alex has a chance of co-owning a bar. During the execution of the plan, however, Tamara gets killed by a policeman, Robert (Andreas Lust), who is thereafter obsessed with what he’s done. He doesn’t know exactly how the killing took place and his inner turmoil affects both his work and his marriage to Susanne (Ursula Strauss). To Alex the shooting was murder (he’s wrong) and he doesn’t want Robert to go on living. Early in the film, the pimp asserts that Alex believes he’s a tough guy but really isn’t. While living with his grandfather in a rural area, where coincidentally Robert and Susanne also live, will Alex turn into a tough guy and avenge himself by killing the policeman?

Even viewing it on DVD, I can see that Gotz Spielmann’s film, which never played in Tulsa, is a terrific work of art.

The effect of being deprived of a lover and thereafter alone is staggering. The scenes of city life in Vienna and then of doings in the countryside are equally compelling. Except for Alex’s grandfather, the people in Revanche are incomplete, stunted, because of the lure of ill-gotten gain, because of drug addiction, because of childlessness (in the case of Robert and Susanne). They face their own failure: Alex himself gets Tamara killed, Robert wishes he hadn’t killed her. Indeed, if the policeman did anything truly wrong, he eventually receives a comeuppance by being cuckolded. He is a pitiable man, and so, in a way, is Alex.

The film is Austrian, the title is French. “Revanche” is “revenge” in French. Spielmann may have given it this title because in France romantic notions about revenge, as about so many other things, were generated over the years. Even revenge against a policeman in the twentieth century–in French Algeria, perhaps?–could be considered as legitimate as revenge against the royal family during the Revolution. Yet Spielmann, I think, rejects such romanticism for his Austrian milieu. It never arises.

(This is a foreign film with English subtitles.)

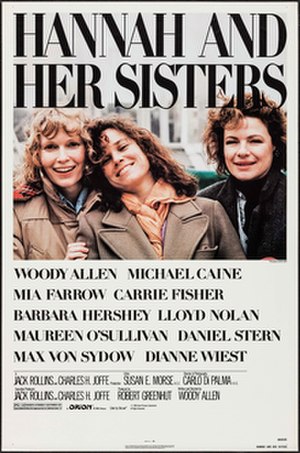

Cover via Amazon