-

The acting in Cecil DeMille‘s The Ten Commandments is not always good, so it’s a wonder the thespians manage to exude as much true spirituality as they do. Not that it is never artificial—of course it is—but the artificiality of the entire picture fails to upend the spiritual feeling DeMille was after.

- Since the ancient Egyptians worshipped many gods, cats included, surely it is unsurprising to find an Egyptian woman, Anne Baxter‘s Nefretiri, worshipping a handsome non-god, Moses (Charleton Heston). Baxter is beautiful, her acting nicely precise in its dreaminess. Debra Paget and Yvonne De Carlo are beautiful too, but do not have much impact here.

- It was inspired of the screenwriters to have Joshua (John Derek) paint lamb’s blood on the doorposts and lintel of the house where Lilia (Paget) is being kept by middle-aged Dathan (that pig!) It means firstborn Lilia doesn’t have to die. Ah, Moses, however, tells the stricken Nefretiri—nothing really goes right for her—that he is unable to save the life of her small son, and yet this is not true. He simply needs to urge her to arrange the painting of lamb’s blood on her doorposts and lintel.

Cropped screenshot of Anne Baxter with Yul Brynner from the trailer for the film The Ten Commandments. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Category: General Page 2 of 272

I wonder whether they’ll ever make a movie about today’s black-on-white violent crime, of which there is a lot. What was made instead, though it was decades ago, was Sam Fuller‘s White Dog (1982), about a dog trained by a sick racist to attack black people.

TV actress Kristy McNichol plays an aspiring thespian who finds the dog, initially lost, and then discovers what he was intended to be. A white dog. Like other Fuller films, this one is moderately unusual but, in addition, it shows that Fuller soundly possessed a mind.

At a training spot for animals used in movies, a black man acted by Paul Winfield painstakingly tries to cure the dog of its ugly instinct. Progress is so frustratingly slow that the dog has time to escape and, yes, actually kills a man. The film shows us the ease with which evil becomes real, becomes evident, and how lost we often are when trying to eliminate it. Fuller’s directing is far from ideal with its camera zooms and clunkiness, but the story’s power to disturb remains. McNichol and Winfield turn out decent, if unspectacular, performances. As always, Burl Ives is agreeably authoritative.

It shouldn’t be this way, but every time a good deed is done in the “inspiring” It Could Happen to You (1994), it seems ersatz. In large part this is because Nicolas Cage, in this Capra-like little film, lacks the liveliness and purity of heart of, say, James Stewart in Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life. Both are morally encouraging guys, but only one is truly authentic.

Ah, but Andrew Bergman‘s movie needs more verity in any case. There is third-rate characterization in Rosie Perez‘s role, and an ending more moralistic than moral (with the punishing of both Perez and Stanley Tucci). The acting is often a letdown except for that of Bridget Fonda, who provides the only depth the film possesses. One critic opined that Fonda “isn’t at her best” in It Could Happen to You. What nonsense. She is superlative.

Military pride and victory, battlefield suffering, religious conviction, and death in all its pervasiveness all meet in the Julien Duvivier film, La Bandera (The Flag, 1935), whose gritty screenplay Duvivier and co-scenarist Charles Spaak adapted from a novel.

The picture concerns a Frenchman called Gilieth who murders a man in Paris (“a piece of crap” he calls him) and then runs away to Barcelona, where he is unemployed and hungry. In order to survive, he joins the Spanish Foreign Legion, though not without a clandestine Spanish detective on his trail. All the legionnaires, Gilieth included, volunteer to fight in the Spanish Civil War, and an agonizing, disastrous experience it is. Can there be—is there—the acquisition of honor in this?

The French actress Annabella, who was married to Tyrone Power, has top billing in this film (she plays an Arab girl whom Gilieth marries), but she is not the star. Jean Gabin is, satisfyingly cast as the one-time murderer. . . La Bandera is now creaky and obstreperous, but also vivid and candid. I would say that at first its attitude is misanthropic, but eventually it does see Gilieth as acquiring honor as it puts a measure of faith in men on the battlefield, as it necessarily respects human risk and endurance. At least the Spanish detective seems to see Gilieth as acquiring honor (or expiation).

(In French with English subtitles)

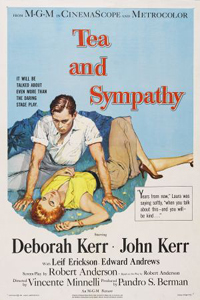

Tom is a college boy who is not very virile, and because of the ridicule and suspicion he elicits, the college headmaster’s wife, Laura, is kind and helpful to him. Laura herself could use some kindness, though, since she is married to a man who, though manly, resists her and is a repressed homosexual. He is seemingly jealous of Tom—a heterosexual, by the way—who knows how to receive and appreciate Laura’s sympathetic care.

The agony associated with what the human heart demands and needs is what Tea and Sympathy (1956)—film by Vincent Minnelli, play and screenplay by Robert Anderson—is about. Properly and knowingly, Minnelli put the play on the screen, and the top-notch cast from the Broadway production (Deborah Kerr, et al.) was used. The result is a truly adult film, i.e. one for an adult sensibility, presented with appreciable power. Kenneth Tynan rightly thought the play a good middlebrow work; no less so is the movie.