From Taiwan, in 1994, came Ang Lee’s Eat Drink Man Woman, whose title might betoken a loopy comedy; but, no, the film is merely a serious comedy, or comedy-drama, not a loopy one. The four-word expression refers to food and sex, and it may well occur to us that in Lee’s film not much gets in the way of “eat drink” (for such is life in a developed country) but much does get in the way of “man woman” (quite common in any country).

The major characters are Chu, a middle-aged widower and master chef, and his three daughters, Jia-Chien, Jia-Jen and Jia-Ning. None of the daughters is married yet or even has a boyfriend, although beautiful Jia-Chien, a white-collar airline employee, attracts the attention of two handsome men with whom she might become only superficially involved, if at all. Jia-Jen is a Christian who teaches chemistry and is virtually regarded as an old maid, but has eyes for a public-school volleyball coach. Jia-Ning is a teenager who works at Wendy’s and gradually wins over a co-worker’s beau.

Physical needs and wants must be tended to; they make up the routine. But Chu wants to know if “eat drink man woman” is all there is to life. A person like the religious Jia-Jen proves it is not, and yet the complete blocking of physical, or sexual, pleasure means the denial of sexual-amorous love. This latter, sexual-amorous love, is on the horizon for Jia-Ning, the youngest daughter, but Jia-Chien, albeit she has been sexually active, is simply groping for it and Jia-Jen is beginning to grope for it (for the second time in her life?) until success occurs.

The film is perfectly, imaginatively directed by Ang Lee—a fine artist—who wrote the script with two other men. An unpredictable, moving story it is, played out by admirable actors. And there is superb music by Mader, sometimes jaunty and sometimes sweet in an Erik Satieish way. To me, this early Lee achievement is one for the ages.

(With English subtitles)

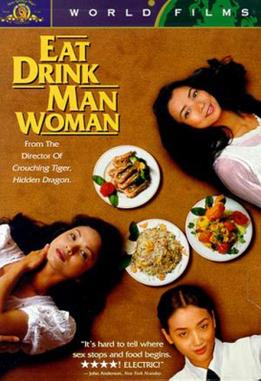

Eat Drink Man Woman (Photo credit: Wikipedia)